Kimball Taylor’s profile on Dean Randazzo ran in the June 2010 issue of SURFER. This version has been slighted shortened and edited.

* * *

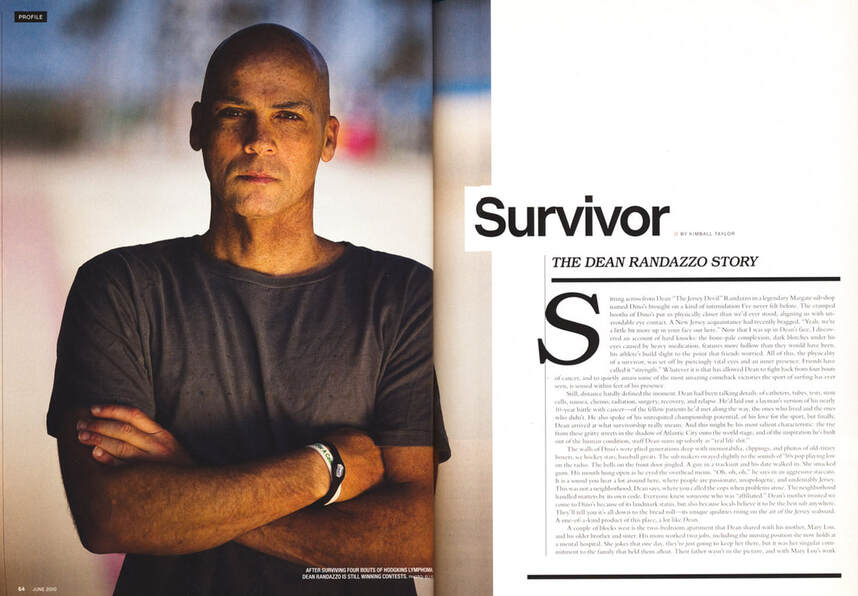

Sitting across from Dean “The Jersey Devil” Randazzo in a legendary Margate sub shop named Dino’s brought on a kind of intimidation I’ve never felt before. The cramped booths of Dino’s put us physically closer than we’d ever stood, and there was unavoidable eye contact. A New Jersey acquaintance had recently bragged, “Yeah, we’re a little bit more up in your face out here.” Now that I was up in Dean’s face, I discovered an account of hard knocks: the bone-pale complexion, dark blotches under his eyes caused by heavy medication, features more hollow than they would have been, his athlete’s build slight to a point that caused friends to worry. Yet all of this—the physicality of a survivor—was set off by piercingly vital eyes and an inner presence. Friends have called it “strength.” Whatever it is that has allowed Dean to fight back from four bouts of cancer, and to quietly amass some of the most amazing comeback victories the sport of surfing has ever seen, is sensed within feet of his presence.

Dean was talking of the details: of catheters, tubes, stem cells, nausea, endless tests, chemo, radiation, surgery, recovery, and relapse. He gave me a layman’s version of his nearly ten-year battle with cancer—of fellow patients he’d met along the way, the ones who lived and the ones who didn’t. He also spoke of his unrequited championship potential, and of his love for the sport. Then finally Dean arrived at what survivorship really means. And this might be his most salient characteristic: the rise from these gritty streets in the shadow of Atlantic City onto the world stage, and of the inspiration he’s built out of the human condition, stuff Dean sums up soberly as “real life shit.”

The walls of Dino’s were plied with generations of memorabilia, clippings, and photos of old-timey boxers, hockey stars, baseball greats. The sub makers swayed slightly to the sounds of ’50s pop hits playing softly on the radio. The bells on the front door jingled. A guy in a tracksuit and his date walked in. She smacked gum. His mouth hung open as he eyed the overhead menu. “Oh, oh, oh,” he says in an aggressive staccato. It is a sound you hear a lot around here, where people are passionate, unapologetic, and undeniably Jersey. This was not a neighborhood, Dean says, where you called the cops if a problem arose. The neighborhood handled matters by its own code. Everyone knew someone who was “affiliated.” Dean’s mother insisted we come to Dino’s because of its landmark status, but also because it is said to produce the best sub sandwich anywhere. They’ll tell you it’s all down to the bread roll—its unique qualities rising on the air of the Jersey seaboard. The Dino sub is a one-of-a-kind product of this place—a lot like Dean.

A couple of blocks west is the two-bedroom apartment that Dean once shared with his mother, Mary Lou, and his older brother and sister. His mom worked two jobs, including the nursing position she now holds at a mental hospital. She jokes that one day, they’re just going to keep her there on the ward, but it was her singular commitment to the family that held them afloat. Their father wasn’t in the picture, and with Mary Lou’s work, Dean and his brother Joe had a pretty long tether. Most often that leeway extended a couple of blocks east to where the wood-pillared Margate pier wades into the Atlantic. Dean and Joe learned to surf together. One weekend, Mary Lou bought them a pair of blue and white Styrofoam belly boards from the local five and dime. One of the board broke right away. “I bought those boards thinking the boys could lay on them,” says Mary Lou. “Before you know it, they saw those guys down at the other beach surfing, and they wanted to stand.” The Randazzo brothers traded off on the remaining board until they did, finless by necessity. Joe and Dean mimicked the older guys; they built friendships and found their places in the Margate scene. They earned the nicknames “Dazer” (Joe) and “Doodoo” (Dean). Joe’s handle stuck with him, but luckily Dean went on to earn others. Today, Joe and Dean disagree on which of them actually owned the first real surfboard in the family, but they each recall its price—$30. It’s said that in both equipment and technique, New Jersey was 10 years behind the times. With no money to speak of, Dean’s equipment usually hailed from a bit further back, including a beaver-tail wetsuit he wore through the winter and the single-fin he rode well into the age of the thruster.

Mary Lou Randazzo moved the family to Somer’s Point, a more residential area of South Jersey that provided Dean with access to a skate park and the boardwalk of Ocean City, a central focus in the Jersey surf world. Tom Forkin, driving-age at the time, first caught sight of 13-year-old Dean at the skate park. He noticed the kid’s wavy afro and skating prowess. Later, driving across the causeway in his weathered pick-up, Forkin came upon Dean in his beaver-tail, riding a bike and carrying a board Dean’s mother remembered as a “real piece of art, made more of duct tape than actual board.” The causeway where Forkin spotted Dean was basically a two-mile bridge with no shoulder. Cars hurtled past within inches. This daring little kid was impressive just in the way he got to the beach. Soon enough, Forkin began to shuttle Dean along with the rest of his crew down to Ocean City’s 7th Street. “If there were some beers cracked in the back of that truck,” says Forkin, “then there were beers cracked. It wasn’t the most child-friendly environment—all those characters going wild in the back. The cops would shoot you for that shit these days.”

On the boardwalk, Dean endured grommet abuse on a level that would be considered criminal by today’s standards. An older kid offered to let Dean try his board. Clearly, this was a trap. Dean couldn’tpossibly imagine generosity on this level. But the older kid convinced him. The drive and acceleration of that new board under Dean’s feet came as such a liberation that he later asked another older kid to use his board. The guy gave Dean 10 minutes, no more. When Dean hadn’t made it in by the 10-minute mark, the guy swam out and punched Dean in the face.

Luckily, there was a strong competitive surfing culture within the 7th Street experience as well. Dean surfed events held by the OCSA (Ocean City Surfing Association) and he progressed quickly. Forkin and the boys introduced Dean to Surfers Supplies owner George Gerlach, who gave Dean a job in the shop. The teenager worked the counter and saved for an employee-discount thruster. Gerlach also took area kids to contests, and to North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras for the Eastern Surfing Association Championships. If he had to, he paid the entrance fee. It wasn’t much as far as sponsorships go, but then Dean never needed a lot.

Meanwhile, he was making a name for himself on the local scene. “His reputation was bigger than he was,” says Adam Wolcoff, a former president of Dean’s small but successful cancer foundation. “But I don’t think he knew it.” A few years younger, Wolcoff remembers that when Dean surfed, he and his peers simply watched. The most classic instance of this phenomenon occurred when Hurricane Charlie came roaring into town. At dawn, the surf was double- to triple-overhead, the wind was light offshore, and the Ocean City Police Department had closed down the entire beach, prohibiting anyone to enter the water. Forkin and a couple friends had already been stopped at the water’s edge by the cops when Randazzo sprinted around the OCPD blockade and launched into the surf. Lifeguards and police got on the bullhorns. On the boardwalk, people stopped to see what was going to happen. As Wolcoff remembers, “Everybody watched Dean getting spit out of barrels, hitting the lip, everything.” When Dean finally came washing into the shorebreak at noon, the crowd erupted. The police descended. The boardwalk crowd loved this too—skill and bravado on Dean’s scale deserved, if not an award, then at least an arrest. There is a blurry scan of a photo taken shortly afterward that Dean’s friends have been passing around ever since. Seventeen years old, the police at his back leading him away, Dean with a big shit-eating grin.

* * *

The phrase goes, “You can’t fling a dead cat without clunkin’ somebody from New Jersey.” But for Randazzo, the road to a professional career was an isolating experience. Friends claim that he went off to California one day and never came back. This isn’t really true, but once he made the NSSA National Team, coached by Ian Cairns, and began to travel, he simply grew beyond the Jersey shore. What he graduated to, however, was a long and hard-scrabble journey. There were successes—renowned surf critic Derek Hynd praised Dean’s early performance at the Coldwater Classic in Santa Cruz, comparing him to Tom Curren and Gary Elkerton. Dean won the occasional event and made some deep impressions with his freesurfing. His cache grew. But there was never much money. Hitchhiking with his board from Oceanside to a contest in Ventura, Dean found himself temporarily stranded in a shady section of Los Angeles. A black man in a beat-up truck pulled over. “Son,” the man says, “you know what you’re doing isn’t safe.” The man then tossed Dean a few bucks for bus fare. It was all the money Dean made on that trip. In Hawaii, he worked at the Sunset Beach Chevron station. He filled the tanks of both visiting and local pros, hoping only to squeak in a few waves between shifts. The job wasn’t enough, however, and Dean stooped to dialing the operator from a public phone booth to claim the phone had stolen his money. For this small deceit, the phone company mailed him checks of $1.50 each time. When Dean arrived in Europe for the longest leg of what would be his qualifying year, he had five dollars in his pocket.

“Every New Jersey kid who competes, or hopes to compete at a pro level, should personally seek out and thank Dean Randazzo,” says Seaside Height’s Sam Hammer. On a very basic level, this is due to the fact that Dean made it—the first male surfer from the Northeastern United States to crack the WCT. In 1996, he scored 10s at Jeffreys Bay, trading gaffs with Rob Machado. He gained a reputation for surfing white-hot when he was on, then melting down just as spectacularly.

He didn’t take failure lightly.

Dean may be the inventor of a flying kick-out during which he punches his board mid-air. “I only started to figure things out halfway through the season,” he says. But without a major sponsor, he was down to the same brand of hard travel he’d found on the WQS. “I wasn’t a conditioned competitor, but if I’d had some sponsorship and guidance, I could have done well. On Tour without any money, I was forced to think about everything but my performance in a heat.”

Dean failed to requalify. The following year he was delivering pizzas for a living the next year. But this began a determined climb back up the WQS ratings. By 2001, he’d linked together a string of victories, and picked up a sponsorship with Body Glove.

The deal was performance-based, and Dean performed. He made the semifinals at Lower Trestles and was looking at another qualifying run for the WCT—except his time he’d have some real sponsorship. “But I think I was sick even then,” Dean says in retrospect.

His fingers had already spent a lot of time probing a lump on his neck. Dean finally had it checked out. A doctor at the local clinic waved him off, suggesting the lump was a reaction to something in the water. Dean was fit, young, and healthy. He continued to travel and compete, but he often felt dragged down. The lump did no get smaller. In Indonesia, he’d taken a fall and been scraped across the reef. The gouges were deep enough for Dean to consider the danger of his occupation. On a hunch, he bought the first medical insurance policy he’d had as an adult. Meanwhile, a second lump developed. He scheduled an appointment with a different doctor. The blood tests that didn’t raise alarm, but a biopsy was performed, and sure enough, the lumps were tumors. Dean, 30 years old, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

“It’s serious,” Dean says now, remembering how he felt at the time, “but you try not to think it is, just so you can get through it.” The only bright spot was Hodgkin’s is potentially curable. First up: chemotherapy. The toxic liquid was injected into his bloodstream with the hope that the treatment would kill the cancer before it killed Dean. If so, they could slowly bring Dean back to health.

Chemo doesn’t hit all at once. It makes patients increasingly ill. At first, Dean was able to handle the dosages and keep on surfing. Always reticent to expose himself, he didn’t want the surf community to know about the illness. He feared what the stigma of disease would do to the only career he’d ever known; He feared losing his deal with Body Glove, the first major sponsor that really believed in him. Three chemo treatments into the regimen, in fact, Dean entered the US Open in Huntington Beach. Both his mother and brother, who he’d sworn to secrecy, watched from the pier as Dean clawed heat-by-heat into the later rounds. He relied on strategy in the ways he’d once relied on strength. And his unexpected rise in the event signaled an achievement that would become emblematic of his life post-diagnosis. Then again, by the time Dean fell out of the US Open, he knew was that he couldn’t carry the weight of the disease alone, and he announced that he had cancer there in Huntington.

Soon the treatment became painful. “So bad you don’t even want to imagine it,” Dean says. At the hospital, rolling his IV drip stand down the hall became the most difficult part of his day and, finally, he couldn’t even do that. The smell of food caused him to wretch. “Diarrhea, fatigue, everything—as ill as you want to be.” Then came radiation treatment each day for a month, leading all the way through his birthday and up to Christmas Eve, when Dean asked the doctors if he could he please have a few days off. “He never complained,” says his mother, Mary Lou. “He never asked, ‘Why me?”’

In remission, Dean focused on two things: he wanted to mount a comeback, but he was also obsessed over his recent history. The details of it played out in his mind. He couldn’t believe his good fortune in gaining insurance before becoming sick. Scrapping together funds for a World Tour bid was one thing, amassing a defense against cancer was another. And on the deepest level, Dean understood that he wasn’t alone in battling cancer. He felt lucky. He knew that most pro surfers, like many young people not living with their parents, didn’t have health insurance. This line of thought, even as he recovered, became the seed of the Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation. The first step was simply buying a book—a kind of “non-profit for dummies.’’ He later called Adam Wolcoff, his old friend from Ocean City, who by that point was a lawyer. Together, along with Joe and Mary Lou, they began to build what they hoped to be a long-lasting aid to others in Dean’s situation. As Mary Lou remembers it, however, “We threw it together in a month.”

* * *

By 2010, Dean had survived four major cancer-related crises.

In 2006, nearly five years after his first diagnosis—a milestone of remission—the cancer returned. And as often happens, it came on with a ferocity it didn’t have before. Mary Lou had always sent Dean, usually in Hawaii at that time, a plane ticket home for Christmas. Like every year, he accepted the gift and made the trip. After dinner a day or two into his stay, Dean told his mother he would be leaving for California and treatment the next day—a new tumor had been discovered in his chest. “I didn’t suspect a thing,” she says. “When he told me, I couldn’t take it. I fell apart.” Since that time, Dean’s undergone more chemo, more radiation, and two stem cell transplants—first with his own stem cells, and then in 2008, with his brother Joe’s. But the bouts with Hodgkins, his time in the hospital, the slew of medications, and his deficit of immunity don’t tell his story nearly as well as the athletic and human successes between them.

When Dean was well again in 2001, during his first big event back on the WQS, he once again made it to the semifinals at Lowers, only to garner a double-interference with Florida’s Damien Hobgood. This sits with him; he should have won the contest. In 2007, while still in recovery from his second bout, he entered the New Jersey Grudge Match, a prestigious event among the best in the Garden State—all young fighters that Dean had a hand in creating—and he climbed to the top of the draw. Nick Bricker, who was judging the event, says, “It was awesome to watch him surf that well, but it was also tough because Dean was so winded between heats.”

Later, Dean would admit that radiation had taken its toll on his lungs, and jogging down the beach felt like sprinting a marathon. In the final, Dean met Matt Keenan, also a previous winner of the Grudge Match. “It was the best I’ve ever seen Keenan surf,” Bricker remembers, “and Dean took him out.” At another event, Dean won his first heat, then scored a 10 and 9.5 in his second heat. When he emerged from the water, Bricker says, “I ran down the beach because I thought he was going to collapse.” Bricker wanted to call an ambulance. The next heat was the expression session, which Dean skipped. “But he came back,” says Bricker, “and won the contest.”

For Dean, however, the real success of this period was the development of the Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation, as it grew from an idea into an organization that raised money for both hospitals and individuals. The foundation raised money for Pipeline charger Jason Bogle and WCT vet Richie Lovett.

In March of 2010, while I made arrangements to travel out to the foundation’s “Freeze for a Cause” contest in Seaside Heights, Dean mentioned that he was going in for an MRI. It was so casual a mention, that I was shocked to learn the scan actually marked a major point in his remission. The results were good. He was still cancer-free. He was 40 years old, an age by which most professional surfers have long retired. But Dean’s goals remained the same as they had for two decades. “He honestly wants to make the World Tour again,” says Tom Forkin, “that’s where his head is at.”

“I asked Dean, ‘Man, what are your plans?”’ says Wolcoff. “And Dean says all he’s ever wanted was one healthy year to find out how far his talent and drive could really take him. But he never got that year.”

Dean’s future, Wolcoff believes, will ultimately be with the foundation. Yet Dean was surfing as strong as ever, and looking to compete and to realize the dreams that have been on hold for so long. Driving through Margate after our subs at Dino’s, I asked him about his plans. He didn’t answer directly but began talking about his work as an advocate. One of the hardest things a cancer survivor can do is return to the cancer ward. It takes such a dogged belief in one’s own chances for success, that to see what the disease is actually doing to others can rattle a survivor. As the namesake of his foundation, Dean returns to cancer wards time and again. He mentioned a four-year-old boy named Nicolas who he’d become close to. They’d had plans to go surfing as soon as Nicolas was well. When the boy died, it broke Dean. “I didn’t want to be an advocate anymore. Not for a long time. But then I slowly thought, ‘You know what? I made his life better.” The Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation doesn’t consider prognosis in deliberating over grant requests, only the needs of the patient. This leaves Dean open to some tough emotional challenges.

A week after my visit to New Jersey, Dean entered a Masters event at Sebastian Inlet. To qualify, a surfer had to be 40 years old or older. Dean had been cagey about his age, suspecting it might sway WQS judges a point here or a point there. It might hinder his sponsorship opportunities. Entering the event was a way of revealing his age to the world, much as he’d announced his cancer in Huntington. He swept the field at Sebastian. Furthermore, he more or less took the result as a given. Challenges to one’s mortality often rearrange focus, but it only strengthened Dean’s.

In hearing all the real and magnified stories about The Jersey Devil traded among his friends and competitors, I began to understand what I found intimidating at Dino’s. It wasn’t the cancer-caused physical attributes, or even what those markings said about mortality. It was Dean’s strength of will. Here was a man who was brought down to zero by disease and the side effects of treatment time and again, but who consistently got back up, paddled out, and won—because he willed it.

Dean puts all this in simpler terms. “I consider myself cured,” he says. “And that’s all there is to it.”

[Photos: Grant Ellis, Dick Meseroll, Kevin Welsh]

* * *

Sitting across from Dean “The Jersey Devil” Randazzo in a legendary Margate sub shop named Dino’s brought on a kind of intimidation I’ve never felt before. The cramped booths of Dino’s put us physically closer than we’d ever stood, and there was unavoidable eye contact. A New Jersey acquaintance had recently bragged, “Yeah, we’re a little bit more up in your face out here.” Now that I was up in Dean’s face, I discovered an account of hard knocks: the bone-pale complexion, dark blotches under his eyes caused by heavy medication, features more hollow than they would have been, his athlete’s build slight to a point that caused friends to worry. Yet all of this—the physicality of a survivor—was set off by piercingly vital eyes and an inner presence. Friends have called it “strength.” Whatever it is that has allowed Dean to fight back from four bouts of cancer, and to quietly amass some of the most amazing comeback victories the sport of surfing has ever seen, is sensed within feet of his presence.

Dean was talking of the details: of catheters, tubes, stem cells, nausea, endless tests, chemo, radiation, surgery, recovery, and relapse. He gave me a layman’s version of his nearly ten-year battle with cancer—of fellow patients he’d met along the way, the ones who lived and the ones who didn’t. He also spoke of his unrequited championship potential, and of his love for the sport. Then finally Dean arrived at what survivorship really means. And this might be his most salient characteristic: the rise from these gritty streets in the shadow of Atlantic City onto the world stage, and of the inspiration he’s built out of the human condition, stuff Dean sums up soberly as “real life shit.”

The walls of Dino’s were plied with generations of memorabilia, clippings, and photos of old-timey boxers, hockey stars, baseball greats. The sub makers swayed slightly to the sounds of ’50s pop hits playing softly on the radio. The bells on the front door jingled. A guy in a tracksuit and his date walked in. She smacked gum. His mouth hung open as he eyed the overhead menu. “Oh, oh, oh,” he says in an aggressive staccato. It is a sound you hear a lot around here, where people are passionate, unapologetic, and undeniably Jersey. This was not a neighborhood, Dean says, where you called the cops if a problem arose. The neighborhood handled matters by its own code. Everyone knew someone who was “affiliated.” Dean’s mother insisted we come to Dino’s because of its landmark status, but also because it is said to produce the best sub sandwich anywhere. They’ll tell you it’s all down to the bread roll—its unique qualities rising on the air of the Jersey seaboard. The Dino sub is a one-of-a-kind product of this place—a lot like Dean.

A couple of blocks west is the two-bedroom apartment that Dean once shared with his mother, Mary Lou, and his older brother and sister. His mom worked two jobs, including the nursing position she now holds at a mental hospital. She jokes that one day, they’re just going to keep her there on the ward, but it was her singular commitment to the family that held them afloat. Their father wasn’t in the picture, and with Mary Lou’s work, Dean and his brother Joe had a pretty long tether. Most often that leeway extended a couple of blocks east to where the wood-pillared Margate pier wades into the Atlantic. Dean and Joe learned to surf together. One weekend, Mary Lou bought them a pair of blue and white Styrofoam belly boards from the local five and dime. One of the board broke right away. “I bought those boards thinking the boys could lay on them,” says Mary Lou. “Before you know it, they saw those guys down at the other beach surfing, and they wanted to stand.” The Randazzo brothers traded off on the remaining board until they did, finless by necessity. Joe and Dean mimicked the older guys; they built friendships and found their places in the Margate scene. They earned the nicknames “Dazer” (Joe) and “Doodoo” (Dean). Joe’s handle stuck with him, but luckily Dean went on to earn others. Today, Joe and Dean disagree on which of them actually owned the first real surfboard in the family, but they each recall its price—$30. It’s said that in both equipment and technique, New Jersey was 10 years behind the times. With no money to speak of, Dean’s equipment usually hailed from a bit further back, including a beaver-tail wetsuit he wore through the winter and the single-fin he rode well into the age of the thruster.

Mary Lou Randazzo moved the family to Somer’s Point, a more residential area of South Jersey that provided Dean with access to a skate park and the boardwalk of Ocean City, a central focus in the Jersey surf world. Tom Forkin, driving-age at the time, first caught sight of 13-year-old Dean at the skate park. He noticed the kid’s wavy afro and skating prowess. Later, driving across the causeway in his weathered pick-up, Forkin came upon Dean in his beaver-tail, riding a bike and carrying a board Dean’s mother remembered as a “real piece of art, made more of duct tape than actual board.” The causeway where Forkin spotted Dean was basically a two-mile bridge with no shoulder. Cars hurtled past within inches. This daring little kid was impressive just in the way he got to the beach. Soon enough, Forkin began to shuttle Dean along with the rest of his crew down to Ocean City’s 7th Street. “If there were some beers cracked in the back of that truck,” says Forkin, “then there were beers cracked. It wasn’t the most child-friendly environment—all those characters going wild in the back. The cops would shoot you for that shit these days.”

On the boardwalk, Dean endured grommet abuse on a level that would be considered criminal by today’s standards. An older kid offered to let Dean try his board. Clearly, this was a trap. Dean couldn’tpossibly imagine generosity on this level. But the older kid convinced him. The drive and acceleration of that new board under Dean’s feet came as such a liberation that he later asked another older kid to use his board. The guy gave Dean 10 minutes, no more. When Dean hadn’t made it in by the 10-minute mark, the guy swam out and punched Dean in the face.

Luckily, there was a strong competitive surfing culture within the 7th Street experience as well. Dean surfed events held by the OCSA (Ocean City Surfing Association) and he progressed quickly. Forkin and the boys introduced Dean to Surfers Supplies owner George Gerlach, who gave Dean a job in the shop. The teenager worked the counter and saved for an employee-discount thruster. Gerlach also took area kids to contests, and to North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras for the Eastern Surfing Association Championships. If he had to, he paid the entrance fee. It wasn’t much as far as sponsorships go, but then Dean never needed a lot.

Meanwhile, he was making a name for himself on the local scene. “His reputation was bigger than he was,” says Adam Wolcoff, a former president of Dean’s small but successful cancer foundation. “But I don’t think he knew it.” A few years younger, Wolcoff remembers that when Dean surfed, he and his peers simply watched. The most classic instance of this phenomenon occurred when Hurricane Charlie came roaring into town. At dawn, the surf was double- to triple-overhead, the wind was light offshore, and the Ocean City Police Department had closed down the entire beach, prohibiting anyone to enter the water. Forkin and a couple friends had already been stopped at the water’s edge by the cops when Randazzo sprinted around the OCPD blockade and launched into the surf. Lifeguards and police got on the bullhorns. On the boardwalk, people stopped to see what was going to happen. As Wolcoff remembers, “Everybody watched Dean getting spit out of barrels, hitting the lip, everything.” When Dean finally came washing into the shorebreak at noon, the crowd erupted. The police descended. The boardwalk crowd loved this too—skill and bravado on Dean’s scale deserved, if not an award, then at least an arrest. There is a blurry scan of a photo taken shortly afterward that Dean’s friends have been passing around ever since. Seventeen years old, the police at his back leading him away, Dean with a big shit-eating grin.

* * *

The phrase goes, “You can’t fling a dead cat without clunkin’ somebody from New Jersey.” But for Randazzo, the road to a professional career was an isolating experience. Friends claim that he went off to California one day and never came back. This isn’t really true, but once he made the NSSA National Team, coached by Ian Cairns, and began to travel, he simply grew beyond the Jersey shore. What he graduated to, however, was a long and hard-scrabble journey. There were successes—renowned surf critic Derek Hynd praised Dean’s early performance at the Coldwater Classic in Santa Cruz, comparing him to Tom Curren and Gary Elkerton. Dean won the occasional event and made some deep impressions with his freesurfing. His cache grew. But there was never much money. Hitchhiking with his board from Oceanside to a contest in Ventura, Dean found himself temporarily stranded in a shady section of Los Angeles. A black man in a beat-up truck pulled over. “Son,” the man says, “you know what you’re doing isn’t safe.” The man then tossed Dean a few bucks for bus fare. It was all the money Dean made on that trip. In Hawaii, he worked at the Sunset Beach Chevron station. He filled the tanks of both visiting and local pros, hoping only to squeak in a few waves between shifts. The job wasn’t enough, however, and Dean stooped to dialing the operator from a public phone booth to claim the phone had stolen his money. For this small deceit, the phone company mailed him checks of $1.50 each time. When Dean arrived in Europe for the longest leg of what would be his qualifying year, he had five dollars in his pocket.

“Every New Jersey kid who competes, or hopes to compete at a pro level, should personally seek out and thank Dean Randazzo,” says Seaside Height’s Sam Hammer. On a very basic level, this is due to the fact that Dean made it—the first male surfer from the Northeastern United States to crack the WCT. In 1996, he scored 10s at Jeffreys Bay, trading gaffs with Rob Machado. He gained a reputation for surfing white-hot when he was on, then melting down just as spectacularly.

He didn’t take failure lightly.

Dean may be the inventor of a flying kick-out during which he punches his board mid-air. “I only started to figure things out halfway through the season,” he says. But without a major sponsor, he was down to the same brand of hard travel he’d found on the WQS. “I wasn’t a conditioned competitor, but if I’d had some sponsorship and guidance, I could have done well. On Tour without any money, I was forced to think about everything but my performance in a heat.”

Dean failed to requalify. The following year he was delivering pizzas for a living the next year. But this began a determined climb back up the WQS ratings. By 2001, he’d linked together a string of victories, and picked up a sponsorship with Body Glove.

The deal was performance-based, and Dean performed. He made the semifinals at Lower Trestles and was looking at another qualifying run for the WCT—except his time he’d have some real sponsorship. “But I think I was sick even then,” Dean says in retrospect.

His fingers had already spent a lot of time probing a lump on his neck. Dean finally had it checked out. A doctor at the local clinic waved him off, suggesting the lump was a reaction to something in the water. Dean was fit, young, and healthy. He continued to travel and compete, but he often felt dragged down. The lump did no get smaller. In Indonesia, he’d taken a fall and been scraped across the reef. The gouges were deep enough for Dean to consider the danger of his occupation. On a hunch, he bought the first medical insurance policy he’d had as an adult. Meanwhile, a second lump developed. He scheduled an appointment with a different doctor. The blood tests that didn’t raise alarm, but a biopsy was performed, and sure enough, the lumps were tumors. Dean, 30 years old, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

“It’s serious,” Dean says now, remembering how he felt at the time, “but you try not to think it is, just so you can get through it.” The only bright spot was Hodgkin’s is potentially curable. First up: chemotherapy. The toxic liquid was injected into his bloodstream with the hope that the treatment would kill the cancer before it killed Dean. If so, they could slowly bring Dean back to health.

Chemo doesn’t hit all at once. It makes patients increasingly ill. At first, Dean was able to handle the dosages and keep on surfing. Always reticent to expose himself, he didn’t want the surf community to know about the illness. He feared what the stigma of disease would do to the only career he’d ever known; He feared losing his deal with Body Glove, the first major sponsor that really believed in him. Three chemo treatments into the regimen, in fact, Dean entered the US Open in Huntington Beach. Both his mother and brother, who he’d sworn to secrecy, watched from the pier as Dean clawed heat-by-heat into the later rounds. He relied on strategy in the ways he’d once relied on strength. And his unexpected rise in the event signaled an achievement that would become emblematic of his life post-diagnosis. Then again, by the time Dean fell out of the US Open, he knew was that he couldn’t carry the weight of the disease alone, and he announced that he had cancer there in Huntington.

Soon the treatment became painful. “So bad you don’t even want to imagine it,” Dean says. At the hospital, rolling his IV drip stand down the hall became the most difficult part of his day and, finally, he couldn’t even do that. The smell of food caused him to wretch. “Diarrhea, fatigue, everything—as ill as you want to be.” Then came radiation treatment each day for a month, leading all the way through his birthday and up to Christmas Eve, when Dean asked the doctors if he could he please have a few days off. “He never complained,” says his mother, Mary Lou. “He never asked, ‘Why me?”’

In remission, Dean focused on two things: he wanted to mount a comeback, but he was also obsessed over his recent history. The details of it played out in his mind. He couldn’t believe his good fortune in gaining insurance before becoming sick. Scrapping together funds for a World Tour bid was one thing, amassing a defense against cancer was another. And on the deepest level, Dean understood that he wasn’t alone in battling cancer. He felt lucky. He knew that most pro surfers, like many young people not living with their parents, didn’t have health insurance. This line of thought, even as he recovered, became the seed of the Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation. The first step was simply buying a book—a kind of “non-profit for dummies.’’ He later called Adam Wolcoff, his old friend from Ocean City, who by that point was a lawyer. Together, along with Joe and Mary Lou, they began to build what they hoped to be a long-lasting aid to others in Dean’s situation. As Mary Lou remembers it, however, “We threw it together in a month.”

* * *

By 2010, Dean had survived four major cancer-related crises.

In 2006, nearly five years after his first diagnosis—a milestone of remission—the cancer returned. And as often happens, it came on with a ferocity it didn’t have before. Mary Lou had always sent Dean, usually in Hawaii at that time, a plane ticket home for Christmas. Like every year, he accepted the gift and made the trip. After dinner a day or two into his stay, Dean told his mother he would be leaving for California and treatment the next day—a new tumor had been discovered in his chest. “I didn’t suspect a thing,” she says. “When he told me, I couldn’t take it. I fell apart.” Since that time, Dean’s undergone more chemo, more radiation, and two stem cell transplants—first with his own stem cells, and then in 2008, with his brother Joe’s. But the bouts with Hodgkins, his time in the hospital, the slew of medications, and his deficit of immunity don’t tell his story nearly as well as the athletic and human successes between them.

When Dean was well again in 2001, during his first big event back on the WQS, he once again made it to the semifinals at Lowers, only to garner a double-interference with Florida’s Damien Hobgood. This sits with him; he should have won the contest. In 2007, while still in recovery from his second bout, he entered the New Jersey Grudge Match, a prestigious event among the best in the Garden State—all young fighters that Dean had a hand in creating—and he climbed to the top of the draw. Nick Bricker, who was judging the event, says, “It was awesome to watch him surf that well, but it was also tough because Dean was so winded between heats.”

Later, Dean would admit that radiation had taken its toll on his lungs, and jogging down the beach felt like sprinting a marathon. In the final, Dean met Matt Keenan, also a previous winner of the Grudge Match. “It was the best I’ve ever seen Keenan surf,” Bricker remembers, “and Dean took him out.” At another event, Dean won his first heat, then scored a 10 and 9.5 in his second heat. When he emerged from the water, Bricker says, “I ran down the beach because I thought he was going to collapse.” Bricker wanted to call an ambulance. The next heat was the expression session, which Dean skipped. “But he came back,” says Bricker, “and won the contest.”

For Dean, however, the real success of this period was the development of the Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation, as it grew from an idea into an organization that raised money for both hospitals and individuals. The foundation raised money for Pipeline charger Jason Bogle and WCT vet Richie Lovett.

In March of 2010, while I made arrangements to travel out to the foundation’s “Freeze for a Cause” contest in Seaside Heights, Dean mentioned that he was going in for an MRI. It was so casual a mention, that I was shocked to learn the scan actually marked a major point in his remission. The results were good. He was still cancer-free. He was 40 years old, an age by which most professional surfers have long retired. But Dean’s goals remained the same as they had for two decades. “He honestly wants to make the World Tour again,” says Tom Forkin, “that’s where his head is at.”

“I asked Dean, ‘Man, what are your plans?”’ says Wolcoff. “And Dean says all he’s ever wanted was one healthy year to find out how far his talent and drive could really take him. But he never got that year.”

Dean’s future, Wolcoff believes, will ultimately be with the foundation. Yet Dean was surfing as strong as ever, and looking to compete and to realize the dreams that have been on hold for so long. Driving through Margate after our subs at Dino’s, I asked him about his plans. He didn’t answer directly but began talking about his work as an advocate. One of the hardest things a cancer survivor can do is return to the cancer ward. It takes such a dogged belief in one’s own chances for success, that to see what the disease is actually doing to others can rattle a survivor. As the namesake of his foundation, Dean returns to cancer wards time and again. He mentioned a four-year-old boy named Nicolas who he’d become close to. They’d had plans to go surfing as soon as Nicolas was well. When the boy died, it broke Dean. “I didn’t want to be an advocate anymore. Not for a long time. But then I slowly thought, ‘You know what? I made his life better.” The Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation doesn’t consider prognosis in deliberating over grant requests, only the needs of the patient. This leaves Dean open to some tough emotional challenges.

A week after my visit to New Jersey, Dean entered a Masters event at Sebastian Inlet. To qualify, a surfer had to be 40 years old or older. Dean had been cagey about his age, suspecting it might sway WQS judges a point here or a point there. It might hinder his sponsorship opportunities. Entering the event was a way of revealing his age to the world, much as he’d announced his cancer in Huntington. He swept the field at Sebastian. Furthermore, he more or less took the result as a given. Challenges to one’s mortality often rearrange focus, but it only strengthened Dean’s.

In hearing all the real and magnified stories about The Jersey Devil traded among his friends and competitors, I began to understand what I found intimidating at Dino’s. It wasn’t the cancer-caused physical attributes, or even what those markings said about mortality. It was Dean’s strength of will. Here was a man who was brought down to zero by disease and the side effects of treatment time and again, but who consistently got back up, paddled out, and won—because he willed it.

Dean puts all this in simpler terms. “I consider myself cured,” he says. “And that’s all there is to it.”

[Photos: Grant Ellis, Dick Meseroll, Kevin Welsh]